Stormé DeLarverie (December 24,[note 2] 1920 – May 24, 2014)[2] was an American activist, singer, drag performer,[3][4] and biracial butch lesbian.[1][5] She was heavily involved in the Stonewall riots. Although there is some debate about which actions are attributable to DeLarverie, along with the sequence of events, she has often been identified as inspiring the crowd to riot.[1][2][4][5][6] She is sometimes specifically identified as the one who "threw the first punch".[2][3][4][5]

Early life[]

Youth[]

Stormé DeLarverie was born in New Orleans in 1920 to a white father and African American mother, who worked as a servant for DeLarverie's father's family.[4][5] She celebrated her birthday on December 24, but was never issued a birth certificate as interracial marriage was against the law at the time.[3][4] DeLarverie was primarily raised by her grandfather, while her father paid for her education.[1]

While growing up, she was so often bullied, attacked, and beaten by peers for being biracial — one incident left her with a leg brace, another resulted in a scar from being left hanging on a fence — that her father ultimately sent her away to private school for her own safety. She also spent some time as a teenager in Ringling Bros. Circus, riding jumping horses side-saddle.[4] At around 18, she realized she was gay and decided to move to Chicago: she said she feared she would be murdered if she stayed in the South.[1][4]

Before Stonewall[]

It was very easy. All I had to do was just be me and let people use their imaginations. It never changed me. I was still a woman. Men's jackets were loose, but the pants were skintight. And if I ever took my jacket off onstage, the dirt was out. But you know the strange thing is, I never moved any different than I had when I was wearing women's clothes. [The audience] only saw what they wanted to see and they believed what they wanted to believe.

Stormé DeLarverie, Stormé: The Lady of the Jewel Box (1987)

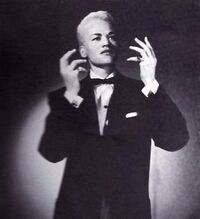

DeLarverie as her drag persona "Stormy Dale".

In the 1940s, DeLarverie sang as "Stormy Dale", dressed as a woman.[1][4] In 1946, she was in Miami visiting Danny Brown and Doc Brenner of the venue Danny's Jewel Box, from which the Jewel Box Revue would later spring, and they needed some help with the show. She had been told not to perform in drag, and that it would ruin her reputation. While she had originally intended on staying only six months, it would be fourteen years before she moved on.[4]

DeLarverie became so celebrated that she began circulating in highly respected crowds, among the likes of Dinah Washington and Billie Holiday.[4] Dressing in traditionally masculine attire, she has been credited with inspiring other lesbians of the era in New York to do the same.[1][4]

Stonewall[]

- Main article: Stonewall riots

It was a rebellion, it was an uprising, it was a civil rights disobedience—it wasn't no damn riot.

Stormé DeLarverie

DeLarverie was present in the early morning hours on June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, New York City, during the police raid that initiated the Stonewall riots. The officers were physically aggressive with the patrons and began arresting employees for liquor license violations and patrons for "cross-dressing".[7] DeLarverie and several fellow butch lesbians attempted to defend their friends, but were beaten by police.[1]

There is debate over her subsequent role in the riot, with some accounts labelling her as the "cross-dressing lesbian" who threw the first punch that initiated the event. DeLarverie stated an officer told her to move along, called her a slur referring to a gay man, and hit her; she punched back. This may or may not have been the so-called first punch.[1][4] She may have been the one who reportedly complained about her handcuffs and was struck with a baton. Allegedly, DeLarverie was dragged into the police wagon and attempted to flee toward Stonewall Inn. When she was pulled back and further beaten by the officers, she yelled to the crowd, "Why don't you do something?"[1] DeLarverie herself, and several eye-witnesses, claimed she instigated the uprising.[2][5]

Regardless of whether she threw the first punch or yelled to the crowd, her presence there is well established and turned her into an icon in LGBTQIA+ history after the riots — which she felt were not so much riots but an act of disobedience and rebellion.[1] These events gave greater momentum to the gay liberation movement in the U.S., and DeLarverie is today revered for her contributions and activism.[4]

Later life[]

DeLarverie's partner, a dancer named Diana, lived with her for about 25 years until Diana died shortly after the events at Stonewall, in the 1970s. According to friend Lisa Cannistraci, DeLarverie carried a photograph of Diana with her at all times.[1] After the passing of Diana, DeLarverie left entertainment almost entirely. Instead, she became a bodyguard for wealthy families during the day and a bouncer (though she did not like that term) at several lesbian bars in the West Village at night. DeLarverie was also known at the time for roaming the West Village vigilante-style.[4] DeLarverie acted as a bodyguard, protecting the revue's transgender women and drag queens.[1] It was an avocation that extended beyond her coworkers; for years, DeLarverie stationed herself as pseudo-guardian to lesbian street kids, looking out for them and doing her best to ensure their well-being. In New York City, she was known for her community spirit and vigilance.[1][3]

DeLarverie was also a well-respected member of the Stonewall Veterans Association, holding several offices there including Chief of Security and Ambassador. She also served as vice president from 1998 to 2000.[5]

DeLarverie later in her life.

In 2010, DeLarverie moved into a nursing home in Brooklyn. With dementia setting in, she did not know she was living in a nursing home, but she retained her memories of the Stonewall riots and her childhood. On June 7, 2012, Brooklyn Pride Inc. honored her at the Brooklyn Society for Ethical Culture, where they also aired the 1987 documentary about her. Two years later on April 24, the Brooklyn Community Pride Center honored DeLarverie "for her fearlessness and bravery." Exactly one month later, DeLarverie died in her Brooklyn nursing home from a heart attack at 94 years old.[5]

Legacy[]

| Expansion needed | |

| This section is incomplete. You can help LGBTQIA+ Wiki by expanding it. |

Notes[]

- ↑ While it is clear that Stormé DeLarverie did not mind being addressed with any pronouns as long as they were used with respect, further research is needed to verify if DeLarverie had different or additional pronouns. This article currently uses she/her.

- ↑ Stormé DeLarverie's exact birthdate is unknown, but this date was the one chosen for celebrating birthdays.